Dear Dad,

This year marks the 20th anniversary of your passing. And 15 years since I finally stopped grieving your death with tears.

But not a single day goes by without me thinking about you and wondering what you think of the woman I’ve become, because even though I am a proud Wiradyuri yinaa, I see your face every time I look in the mirror.

I see your blue eyes and your broad nose. Sometimes I see your fiery, Austrian temper too.

And every single time I’m introduced as Dr or Prof Heiss, I remind myself I’ll never change my name because Heiss is my connection to you, but more importantly, Heiss means hot in German. And I like being Dr Hot.

I wonder what you think of me being a romcom author, when you only ever read westerns yourself. Westerns, on the bottom rung of the literary ladder, even lower than rom coms, which still sell more than many other genres. You’d be happy to see my royalty statements because you always worried about who would take care of me, when I didn’t have a husband. I always told you that I could take care of myself. And FYI, I did spend my wedding money on a fantastic book launch for Not Meeting Mr Right, with a band and open bar all night. I’m not sure you would’ve approved of that.

You told me to follow my dreams, to do what made me happy, as you did, as a carpenter. But when I quit my full-time job to write my first book, you were flabbergasted, saying, “Yes, I said follow your dreams, but I never said, don’t have a salary.’

You’re with me every day, Dad, so maybe I don’t need to write this letter, but I have a few memories, moments in time that have always stayed with me, times when I could’ve said things better. So, I’m saying them now.

For instance, when I was in second grade, 1976, at St Andrew’s Malabar, and the school was preparing for multicultural week, I said proudly, ‘My father is Austrian and he can yodel, and yes, he will come to class and do that.’

The words I’d wished I’d said, or the words you wished I’d said, apparently, are ‘My father is Austrian, but he cannot yodel and would never come to class and do that.’

It was very generous of you though, to then lead the working bee at school that year, and hang blackboards instead. Maybe you whistled occasionally that weekend, but never did you yodel.

When I was suspended twice in high school, once for drinking at a school dance, rather than trying to explain to you and Mum that it was my first time, while others had done it on so many occasions, the words I’d wished I’d said are, ‘I’m sorry I disappointed you Dad, I’m sorry I shamed you and Mum.’

Maybe if I’d said those words, then I wouldn’t have been grounded for what seemed like the rest of my teenage years.

When I was backpacking and needed you to send me money – IOUs you kept a detailed track of - you suggested I needed to stop drinking champagne while I was on a beer budget. Rather than complaining that beer was also expensive for a backpacker, the words I’d wished I’d said were, ‘Danke, Dad, I appreciate it. I love you for helping me out. I will pay you back.’

In the 90s when you drove me to marches against black deaths in custody, and told me not to get arrested, because you didn’t want me to have a record, I responded with, ‘Have your cheque book ready to bail me out, Dad.’

You did not laugh.

The words I’d wished I’d said were, ‘Thank you for teaching me to stand up for my beliefs. For what is right. And thank you for making the pole to hang the Aboriginal flag from, as we marched.’

And we both know, Dad, you would always bail me out of any mess I got myself into.

In 1998 I published a poem about being a bicultural blackfella, that you read as offensive to, and dismissive of you. The words I’d wished I’d said that night when I cried at the kitchen sink, are ‘You’re my hero, Dad, and I am proud your blood runs through my veins.’

In 2001, when you turned up to my PhD graduation in a three-piece suit and bought me every piece of UWS paraphernalia on sale, I shouldn’t have asked if you’d won the lottery. But you were always so thrifty, and being so free with your hard-earned money was not something I saw often.

But the words I’d wished I’d said are, ‘Thank you for the endless sacrifices you and Mum made so that all your children had the best education you could provide. Thank you for being proud of me. Because I only went through the pomp and pageantry of the graduation for you and mum.’

As I move into my new home, I take with me only one piece of furniture you made for me. Out of all the chests of drawers, the desks, the bookcases, dining tables and anything else you could fashion out of wood, I held onto most of them for as long as I could.

Some pieces were refashioned from council chamber doors or cast offs you found on street cleanups. All were repurposed with love and always with a special kind of thriftiness which to your great frustration, I didn’t subscribe to, till later in life.

When you offered to make me a filing cabinet, which I kept for a long time, and asked enthusiastically, what colour I wanted you to paint it, I said, “I don’t care, paint it orange!’ And so, you did.

The words I’d wished I’d said are ‘Thank you, Dad, maybe paint in black?’ which you ended up doing, some years later.

I talk about you with mum a lot, Dad, as she slips further into dementia, she remembers you as Joe the carpenter, Seppi, Poppy, my dad, and her true love.

And tonight Dad, in front of all these good-looking witnesses, as I stand on Awabakel land, I just want to say now the words I’d wished I’d said, on many, many occasions, when you were alive, and I had the chance.

Just as I was always your favourite, you were, and will always be, my hero.

***

Dear Dad was first presented at the 2025 Newcastle Writers Festival as part of Better Off Said: Eulogies for the Living and Dead, a spoken-word salon celebrating words, stories and human experiences.

Better off Said is presented by Emilie Zoey Baker and Marieke Hardy.

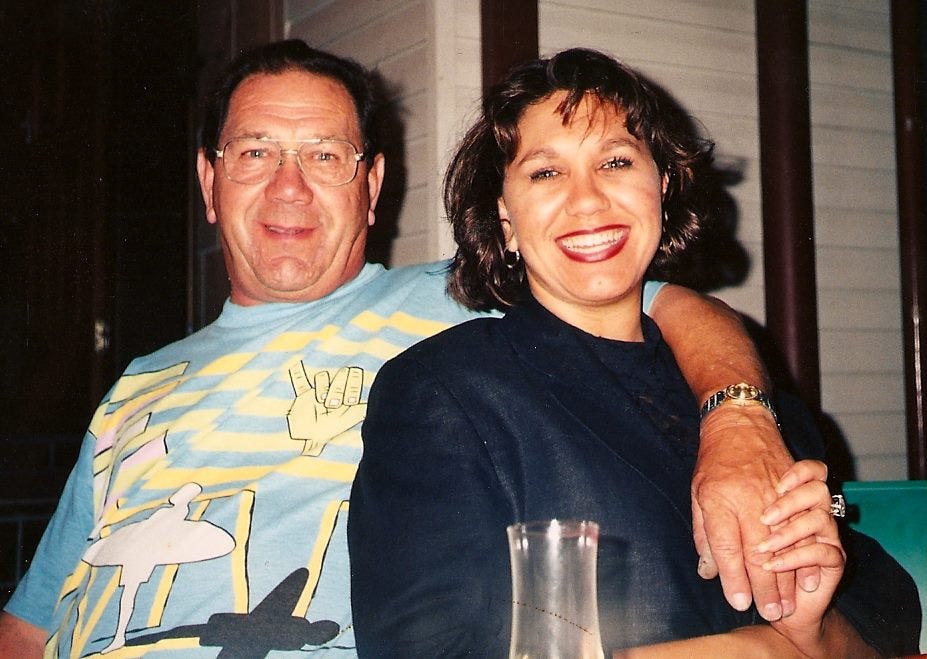

A beautiful letter Anita! Your Dad no doubt would be Hot with the energy of proudness for the woman you are! And that's a stunning photo of you two. X

Well, that made me cry. ❤️